At first meeting, garden designer Brandon Tyson and homeowner Amy Harmon knew they had found kindred spirits in one another—high-energy, über-creative and passionate about their interests. By happy coincidence, both are also complete and unabashed plant nuts. It was kismet.

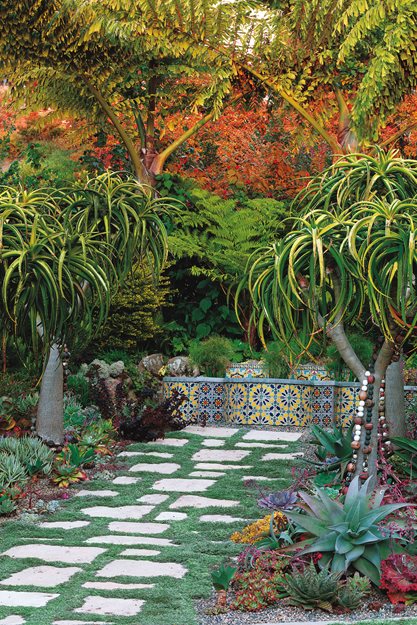

A pair of Himalayan fishtail palms (Caryota gigas, grown by a friend from seed) towers over the garden’s water feature. Instead of a typical allée of cypress trees leading to the fountain, Tyson gave things a twist by choosing Dr. Seuss-like tree aloes (Aloe barberae, syn. A. bainesii), underplanting them with a glittering assortment of succulents. The effect is of a Persian paradise garden. Photo by: Marion Brenner.

Even before Harmon and her family moved into their 1930s Mediterranean-style house in the Berkeley Hills, she already had her sights set on creating a garden with enough panache to match the nearly untouched interior, with its original D&M tile work and wrought-iron light fixtures. In Tyson she found a designer who was a bull’s-eye fit. As Tyson says: “I’m drama driven. I want people to be drawn to a garden and surprised by it. I’m the Cecil B. DeMille of the plant world.” Witness the “undersea garden” at the Harmons’ where Strelitzia juncea and Aeonium take the place of corals and anemones.

That’s not to say Tyson is over the top. He knows exactly how far to push the boundaries, which is what gives his gardens their dynamic tension and sense of play. At the Harmon project, he explored what he calls “deconstructed formalism,” where conventional elements are challenged by the choice of material. For example, he opted for quirky, mop-topped tree aloes as an allée leading to the fountain rather than the expected cypress, and for a hedge to screen the property from the street he used Azara dentata, an evergreen shrub with yellow flowers that smell delectably like chocolate.

As far as sheer theatrics, Tyson readily admits he’s fond of immediate gratification and employs a crane to bring in plant material the way other garden designers might use a hand truck. And he will search high and low for just the right specimens: like the Himalayan fishtail palms a friend had grown from seed that Tyson had been eyeing for 20 years, hoping someday to find a garden as worthy as the Harmons’ to give them a home. Or the rare Chilean wine palm (Jubaea chilensis) Amy Harmon was intent on having that Tyson fortuitously found for sale when the president of the Northern California Chapter of the International Palm Society was dismantling her collection.

Though the garden is small, Harmon wanted pathways and places to sit to appreciate the plantings. Here an antique bench (a gift to Harmon from her husband) looks over architectural Kalanchoe thysiflora and a yellow-flowered groundcover of brass buttons (Cotula lineariloba). Photo by: Marion Brenner.

Despite the primo selections, for Tyson the garden is more than an assembly of plants: “It’s a string of memories; each plant has a story.” It’s also decidedly not a collector’s garden. “There are very few ‘ones’ in the garden,” says Tyson, who is impassioned about weaving together colors and textures—Abutilon, Freesia, Clivia, Sparaxia, Cuphea. For Tyson, it’s like working with fabric. And no wonder, since prior to entering the world of garden design, Tyson studied textile design. He still falls into using textile terms when he talks about gardens, saying something looks like silk or hemp—“It’s just the way I see things.” The layering of this “fabric,” from the trees down to the groundcovers, creates what Tyson calls a “bubble.” “When you come into one of my gardens, you’re in another place and time. Once you’re captured in the bubble, it’s about the garden and not about you.”

Tyson could have found no more appreciative audience or simpatico confederate than Amy Harmon, who has been a client unlike any other. From Tyson’s viewpoint, “Amy is extremely knowledgeable—she really keeps me on my toes.” The two of them routinely collaborated on all aspects of the garden. Says Harmon, “I would get excited about certain plants, like species tulips, and really research them.” Then she and Tyson would go on the hunt. And Harmon feels the process of building and maintaining the garden has been her education as a gardener. At the beginning she had one vision in mind for sure—no roses or lawn. Now she’s pruning her own topiaries among the citrus collection in the backyard (with a little motivation from South Carolina topiary artist Pearl Fryar, another self-taught gardener).

In her extensive travels, Harmon has visited a wealth of gardens, but it was at the outré Lotusland in Santa Barbara that she found particular inspiration for her own. And she became intrigued with the notion of a paradise garden, an oasis from the busy outside world (an idea in keeping with Tyson’s bubble concept) with a meandering pathway that prompts you to focus on each individual plant. She and Tyson agreed that the logical centerpiece should be a fountain, an essential element in Persian and Mediterranean gardens. Tyson had a certain look in mind and asked Amy and her husband Cyrus to find their favorite fountain in the world for the project. They tracked down one they had seen in a book, located in the courtyard of the Andalusia Courtyard Apartments in Los Angeles, designed by Arthur and Nina Zwebell in 1926. Working only from photos, their contractor, Ken Cottrell, managed to duplicate it almost exactly.

For the fountain’s surface, Harmon was resolved to use tiles in the tradition of the 1920s and ’30s, the “golden period” of California tile companies. She was in luck to find Diana Watson of Native Tile & Ceramics, who makes reproductions of D&M Tile—the same as those found inside the Harmon home. The resulting water feature is the focal point of the garden: an exotic, paradisiacal nexus.

Stalklike ceramic sculptures by Berkeley artist Marcia Donahue look alive, emerging from a tapestry of black-foliaged Aeonium ‘Zwartkop’ and Banksia spinulosa ‘Schnapper Point’, and intentionally mimick the timber bamboo in the background. Photo by: Marion Brenner.

To liven up the garden further, Tyson and Harmon introduced sculptural pieces by Berkeley artist Marcia Donahue: a custom turtle spitter for the fountain, ceramic fish, giant beads strung on the tree aloes, and upright stalks that appear to be a cross between the nearby Arisaema and giant timber bamboo. The playfulness of the garden is not lost on the Harmon children, Olivia and Mark. (Olivia, by the way, is convinced there are fairies living there.)

Indeed it’s been a magical experience for Tyson, who has worked mostly in Marin County and was hungry for a Berkeley project. Much to his surprise (having designed gardens predominantly for very private properties), the rest of Berkeley seemed almost as fascinated by the building of the garden as he and Harmon. Neighborly Berkeleyites frequently stopped by to check on its progress and readily offer opinions, especially when Tyson was putting in the narrow bed up by the road. “I was amazed by people’s reactions,” says Tyson. “The garden caused quite a stir.”

For his next project, Tyson is going back to his roots in Georgia, having bought a second home 60 miles from Savannah. Originally from the small town of Albany, he can trace his gardening instincts to both grandmothers, one in North Georgia who favored peonies, and one further south who excelled in growing subtropical plants. The difference in the two intrigued him from an early age, and he feels the South pulling at his heartstrings. He’s primed to go “hammer and tongs” into building a new garden, and having home bases east and west seems to him like the best of both worlds: “Going back and forth will be like traveling to a foreign country.” The yin and yang of bicoastal living should provide grist for much drama to come.